Cole Vogt, Gian Zignago, and Jude Huck-Reymond

May 10th, 2023

Abstract

Topology is a branch of mathematics concerned with the properties of space that are preserved under continuous transformations, such as stretching or bending. In its early development, topology was primarily concerned with the study of curves, surfaces, and other geometric objects in two-dimensional (2D) spaces [5]. The study of topology soon extended to higher dimensions, including three-dimensional (3D) spaces. 3D topology deals with the properties of 3D objects such as volumes, surfaces, and edges, and explores the relationships between them [5]. As this field has evolved, it has drastically deepened our understanding of mathematical structures and has contributed significantly to other disciplines, making it a vital area of research in contemporary mathematics [5]. Active materials have a variety of variables that are effected by their topology such as adaptability, responsiveness, and energy efficiency. This makes them ideal for use in various industries related to material science. Modern technology has witnessed a growing reliance on active materials due to their ability to change properties in response to external stimuli. Current research trends in active materials focus on the development of new materials with enhanced properties, improved manufacturing techniques, and applications in many different industries. This paper aims to explore the connections between 3D topology and active materials. The investigation will involve identifying key factors that link these two fields and examining the impact of 3D topology on the properties of active materials. It will also delve into the applications of 3D topology in the design and development of active materials. Lastly, the paper will discuss the potential of 3D topology for driving future advancements in active materials research.

1. 3D Topology

The analysis of 3D topological structures and spatial objects is a significant area of research in mathematics and related disciplines. Effective techniques for spatial analysis and efficient data structures for representing and manipulating these objects are essential to gain a deeper understanding of their properties and relationships. This section presents an overview of various spatial analysis methods and data structures, exploring their key characteristics, constraints, and applicability in different scenarios.

1.1 Spatial Analysis

Spatial analysis plays a crucial role in the study of 3D topological structures and spatial objects. It enables us to examine the geometric properties and relationships between different components of objects. The key aspects of spatial analysis include space partitioning, object components such as volumes, faces, or surfaces, and construction rules such as planarity and intersection constraints [1]. These elements guide the formation of valid topological structures and help maintain their mathematical properties. In the following sections, we cover various frameworks for representing spatial relationships and spatial operators that facilitate efficient spatial analysis and processing of 3D objects [1].

1.1.1 Frameworks for Representing Spatial Relationships

Spatial relationships can be represented using three key methods: metric, order, and topology [1]. The metric employs computational strategies to compare numerical data associated with object locations [1]. The order method uses mathematical relations to establish a ranking system using structures such as trees [1]. The topology approach, indifferent to object distances, focuses on the neighboring aspects of objects and their components [1]. This makes the topological method suitable for managing spatial relationships digitally. Researchers have developed several different approaches to understanding spatial relationships.

Figure 1. Possible Relationships Between 3D objects [1]

1.1.2 The 9-Intersection Model

The 9-intersection model, proposed by Egenhofer and Herring, utilizes the notions of general topology for topological primitives to investigate the interactions of spatial objects [2]. Topological primitives of a spatial object can be defined for different models. The basic criterion to distinguish between different relations is the detection of empty and non-empty intersections between topological primitives [2].

The intersections are focused on the relationships between interiors, exteriors, and boundaries of 2D objects. More specifically, the 9-Intersections are [2]:

- Interior(A) ∩ Interior(B)

- Interior(A) ∩ Boundary(B)

- Interior(A) ∩ Exterior(B)

- Boundary(A) ∩ Interior(B)

- Boundary(A) ∩ Boundary(B)

- Boundary(A) ∩ Exterior(B)

- Exterior(A) ∩ Interior(B)

- Exterior(A) ∩ Boundary(B)

- Exterior(A) ∩ Exterior(B)

This framework can be extended into three dimensions by considering the same intersections for 3D properties such as volumes, surfaces, and edges. Consider the same 9 intersections for two spatial objects but for volumes A and B, surfaces A’ and B’, and edges A’’ and B’’. The 3D extension of this model is called the 27-Intersection model and provides precise descriptions of the relationships between objects [6].

1.2 Spatial Operators

Spatial operators play a critical role in the manipulation and analysis of spatial data in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) [2]. These operators can be categorized into several groups based on their function and the type of data they process [1].

In order to ensure the accuracy and consistency of spatial data, it is essential to develop operations that construct and update data structures. These operations can include organizing data according to planarity, convexity, and discontinuity [1]. Additionally, consistency check operators must be implemented to validate objects, such as ensuring that polygons are closed and that nodes and lines maintain appropriate relationships [2]. Furthermore, 3D overlay and editing operations enable the addition, deletion, and updating of cells within the data structure [1].

1.2.1 Specialized Operations

Apart from constructing and updating data structures, GIS must also provide operations such as selection, navigation, and specialization [1]. Selection operations allow users to retrieve specific data based on semantic, geometric, or topological criteria [3]. Navigation operations assist users in traversing spatial data, while specialization operations pertain to the further refinement or transformation of data [2].

Spatial operations can be broadly classified into the following categories [1]:

- Metric operations: These are based on the shape and size of objects and may involve computations such as distance, volume, area, and length measurements.

- Position operations: These are based on the position of objects, such as identifying objects within a specific area.

- Proximity operations: These create new objects based on geometric characteristics, such as buffers and convex hulls.

- Relationship operations: These rely on spatial relationships, including neighboring operations and overlays.

- Network operations: These involve spatial relationships, geometries, and further processing, such as route planning.

- Visibility operations: These are based on geometric characteristics and further processing, including line-of-sight analysis.

- Semantic operations: These selections are based on semantic characteristics of the data.

- Mixed operations: These selections involve both geometric and semantic characteristics.

1.3 Data Structures and Spatial Analysis

Data structures significantly affect operations related to the spatial relationships between objects. Certain structures may be more competent for executing specific queries than others. Furthermore, it’s crucial to remember that spatial analysis can also be conducted on geometric models. Many relational Database Management Systems (DBMS) support spatial objects within geometric models and provide numerous spatial operations [1]. In subsequent sections, we’ll delve into various data structures specifically designed to store and manage 3D spatial objects, which enhances efficient spatial analysis and processing [3].

1.4 Structures Maintaining Objects and Relationships

There exist two primary structures that are dependent on the components of objects and the relationships between objects respectively. Here, we discuss the advantages and disadvantages of various models for representing 3D topological structures and spatial objects, highlighting the trade-offs associated with their design and implementation.

1.4.1 Formal Data Structure (FDS)

The Formal Data Structure (FDS) is a strategy for representing 3D spatial objects that employ 12 conventions dividing physical objects into three basic levels: the Feature (Thematic Class), four Elementary Objects (Point, Line, Surface, and Body), and four Primitives (Node, Arc, Face, Edge) [1]. FDS imposes restrictions like non-intersection between arcs and faces, but allows singularities, meaning arcs and nodes can exist within faces or bodies. Edges in FDS delineate the borders of faces and determine their orientation. To ensure consistency, arcs must be straight, and faces need to be planar [1].

1.4.2 Tetrahedral Network (TEN)

The Tetrahedral Network (TEN) is a data structure similar to the FDS but uses a set of four primitives: tetrahedron, triangle, arc, and node [1]. In TEN, a body comprises tetrahedrons, a surface consists of triangles, a line is made up of arcs, and a point includes nodes [1]. The arrangement of primitives is such that each node forms part of an arc, each arc is part of a triangle, and each triangle is part of a tetrahedron [1]. Unlike FDS, TEN disallows singularities, leading to a more restricted representation. TEN has modeling stage issues, as it necessitates the complete subdivision of space into tetrahedrons, including the insides of objects like buildings and open spaces [1]. This division is impractical for 3D man-made objects. TEN is ideal for models visualizing surfaces, as they maintain triangles beneficial for displaying graphic information. TEN’s disadvantage is its significantly larger database compared to other representations, plus the need for special processing of unnecessary tetrahedrons [1].

1.4.3 Tuple Model (Relationship Oriented)

The Tuple Model is a relationship-oriented data structure which defines cells and cell complexes. A k-cell complex is a union of all the k-dimensional cells and lower-dimensional cells. For example, a 2-cell complex would include 2-dimensional cells (like faces of a 3D object), as well as 1-dimensional cells (like edges) and 0-dimensional cells (like vertices or points)[1]. Mesgari later extended the model to allow for singularities within the 3D structures [4]. These singularities can be, for example, a 0-cell inside a 2-cell (a point inside a face), a 2-cell inside another 2-cell (a face with a hole), or a 3-cell inside another 3-cell (a volume with a tunnel) [1]. With these extensions, any spatial object can be represented as a set of tuples, with each tuple containing information about the 3-cell, 2-cell, 1-cell, and 0-cell components [1]. This means that the representation of cells is implicit, rather than explicitly defining each cell’s properties. The tuple model also allows for cells of arbitrary shapes, making it a flexible way to construct and represent various 3D structures [1].

The cell tuple data structure provides the largest spectrum of topological relations between cells and complex cells, making it promising for modeling 3D spatial objects. Moreover, due to its solid mathematical foundations, maintenance is relatively simple. However, the tuple representation lacks any indication regarding the order of cells, necessitating supplementary records to establish the order.

1.5 Considerations

An important aspect to consider when comparing different models is the trade-off between flexibility and complexity. For instance, allowing an arbitrary number of nodes per face can be advantageous for modeling complex 3D objects like buildings, as it avoids unnecessary partitioning and represents objects using boundary faces. However, this flexibility may lead to visualization problems, as rendering engines typically handle only triangles. Moreover, consistency checks become more complex as the number of nodes per face increases.

Similarly, the relationship between face and body in some models can be convenient for navigating through 3D objects but may lead to the storage of non-significant data, such as “open air” being stored as a rigid body.

In summary, the choice of an appropriate model for representing spatial objects depends on the specific requirements and constraints of the application. Each model offers unique advantages and disadvantages, and understanding these trade-offs is essential for making informed decisions when working with 3D spatial data.

2. Active Materials and 3D Topology

Active materials are a class of materials in physics that can convert various forms of energy, such as thermal, electrical, or chemical, into mechanical energy, leading to changes in their shape, size, or other physical properties. Examples of active materials include shape-memory alloys, piezoelectric materials, and electroactive polymers. The study of active materials often involves examining their 3D topology, as this provides insights into the spatial relationships and structural properties that influence their behavior.

2.1 Types of Active Materials

- Shape-memory alloys: These materials can undergo a reversible phase transformation, allowing them to return to their original shape after deformation when exposed to a certain stimulus, such as heat or stress.

- Piezoelectric materials: These materials generate an electric charge when subjected to mechanical stress, and vice versa, deforming when exposed to an electric field.

- Electroactive polymers: These materials can change their shape, size, or stiffness when stimulated by an electric field, making them useful in applications such as sensors, actuators, and artificial muscles.

2.2. 3D Topology in Active Materials

- Structural analysis: The 3D topology of active materials provides insights into their spatial relationships and structural properties. By analyzing their geometric, topological, and semantic characteristics, researchers can better understand the mechanisms underlying their behavior and develop more efficient and effective applications.

- Spatial relationships: The spatial relationships within active materials, such as the arrangement of atoms, molecules, and other structural components, play a crucial role in determining their properties and performance. For example, the lattice structure of shape-memory alloys influences their ability to undergo phase transformations, while the alignment of piezoelectric domains affects the material’s piezoelectric response.

- Topological defects: In some cases, the topology of active materials may contain topological defects, which are irregularities in the spatial arrangement of their structural components. These defects can significantly impact the material’s properties and behavior, often serving as the driving force behind their active responses.

- Simulation and modeling: 3D topology can be utilized in the simulation and modeling of active materials, enabling researchers to predict their behavior under various conditions and optimize their performance. This can be achieved by employing spatial operators and GIS techniques, such as metric, position, proximity, and relationship operations, to manipulate and analyze the 3D topology of these materials.

In summary, the 3D topology of active materials plays a crucial role in understanding their spatial relationships and structural properties. By studying their geometric, topological, and semantic characteristics, researchers can gain valuable insights into the mechanisms behind their behavior and develop more effective applications. Furthermore, GIS techniques and spatial operators can be employed to simulate and model the behavior of these materials, enhancing their performance and utility in various fields.

2.3 Active Matter

Active materials are a class of materials unlike any other with the main ingredient being active matter [30]. Active matter is distinguished because its components are independently consuming energy and exhibiting complex behaviors; consolidating these components brings forth even more complex and coordinated patterns [8]. One of the most interesting aspects of active matter is the emergence of collective behavior from the interactions between the individual components. This can give rise to phenomena such as phase transitions, pattern formation, and self-organization [13][31][19]. Active matter comes in a variety of forms, ranging from artificial to completely natural [18].

2.3.1 Organic Active Matter

One type of active matter that is commonly seen in nature is a group of organisms that move as one; this could be a flock of birds, a herd of animals, a colony of insects, or a school of fish. All demonstrate the condition that each of the individuals independently consumes energy, yet as a whole, the unification of these components creates a mass that acts as if its one organism. Researchers have identified simple rules that govern the motion of each bird, such as “steer to avoid collision with nearby flockmates” [30] and “move toward the average heading of nearby flockmates” [31]. When many birds follow these rules, they can form complex and coordinated patterns that resemble fluid dynamics. Similarly, in the case of schools of fish, individual fish are known to respond to visual and other sensory cues from their neighbors [7], leading to the emergence of collective behaviors such as schooling and swarming.

Figure 2(a) and 2(b): (a) depicts a flock of birds and (b) depicts a school of fish. Both groups move as one brain, but independently consume energy; this exhibits the qualities of active matter [21].

Yet another example is seen taking place naturally on a microscopic scale. Bacteria are a set of microorganisms that exhibit the properties of active matter through swarming; this is a coordinated movement that allows the colony to uniformly explore and spread into new environments in an efficient manner [30][8]. Neurons in the brain demonstrate similar behavior; the interactions between neurons and their environment, including other neurons and the surrounding extracellular matrix, can give rise to a wide range of collective behaviors and emergent phenomena [9]. Neurons can synchronize their activity to generate rhythmic oscillations at various frequencies, which are thought to play a role in many cognitive processes such as attention, memory, and perception [9]. In addition, waves of activity can propagate through the network, allowing information to be transmitted rapidly and efficiently across long distances [9].

2.3.2 Inorganic Active Matter

An inorganic example is self-propelled colloidal particles. These are microscopic particles that can move autonomously by converting available energy into directed motion. These particles are typically made of a magnetic material and are actuated by an external magnetic field. By modulating the magnetic field, the particles can move in a particular direction or assemble into complex structures. These particles are used in liquid environments and are typically made up of metals, polymers, or ceramics. They are being used in drug delivery, microfluidics, and materials science [30][12][20].

Figure 3. Displays the process under which self-propelled colloidal particles undertake in order to construct these complex structures. The Janus spheres have 2 regions with opposing properties, such as hydrophobic and hydrophilic, in order to combine and propel [29].

2.4 Topological Defects

Topological defects are another fascinating phenomenon of active materials. They are regions of the material where the orientation is skewed sharply compared to the surrounding regions. There are different types that can arise depending on the symmetry and dimensionality of the material. The primary kinds are singularities, vortices, dislocations, and topological solitons.

2.4.1 Singularities

Singularities arise when the individual components of the material move in different directions or rotate in opposite directions, leading to regions where the orientation of the components is not well-defined. Singularities can occur in a variety of active materials, including liquid crystals, gels, and even living cells [30][12][8]. The emergence of such a defect can lead to complex flow patterns or changes in energy dissipation. They can even lead to the formation of vortices [9][13].

Figure 4. Depicts a singularity, where the surrounding matter is pulled into the singularity in the middle. Can be compared to the structure of a black hole [26].

2.4.2 Vortices

Vortices are points in the material which act as an axis of rotation for the surrounding matter. Vortices can occur in a variety of active materials, such as liquid crystals, and superconductors, and even in biological systems such as swarming bacteria or flocks of birds [12][8][9]. The appearance of these can lead to the formation of flow patterns that are different from those observed in an otherwise continuous flow, which in turn disrupts energy distribution [12][13].

Figure 5. (a), (b): (a) portrays a vortex, which has the surrounding matter rotate around the core. While (b) displays an antivortex, which has the surrounding matter travel toward the core in two opposite directions and out of the core in perpendicular directions [28].

2.4.3 Dislocations

Dislocations are areas of the lattice that are sharply shifted away from the surrounding matter. The main cause is when the material is subjected to external stresses or strains[14][15]. Dislocations are classified based on their geometry and the direction of the slip that causes the misalignment; the most common types of dislocations are edge dislocations and screw dislocations [14]. Edge dislocations occur when the displacement emerges when the lattice is displaced along a plane perpendicular to the one-dimensional defect. Typically this is caused by a mismatch in the size of two adjacent crystals or grains [14]. Screw dislocations, instead of being a one-dimensional line, are three-dimensional, with components displaced in a helical pattern. These are caused by the application of shear stress, or force applied parallel to the material [14]. Both types of dislocations can affect the mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties of materials [14][15].

Figure 5. Displays the structure of a topological dislocation, specifically in a crystal. A row of atoms does not appear where it should, and no rearrangement can allow for a homogenous structure to form [22].

2.4.4 Topological Solitons

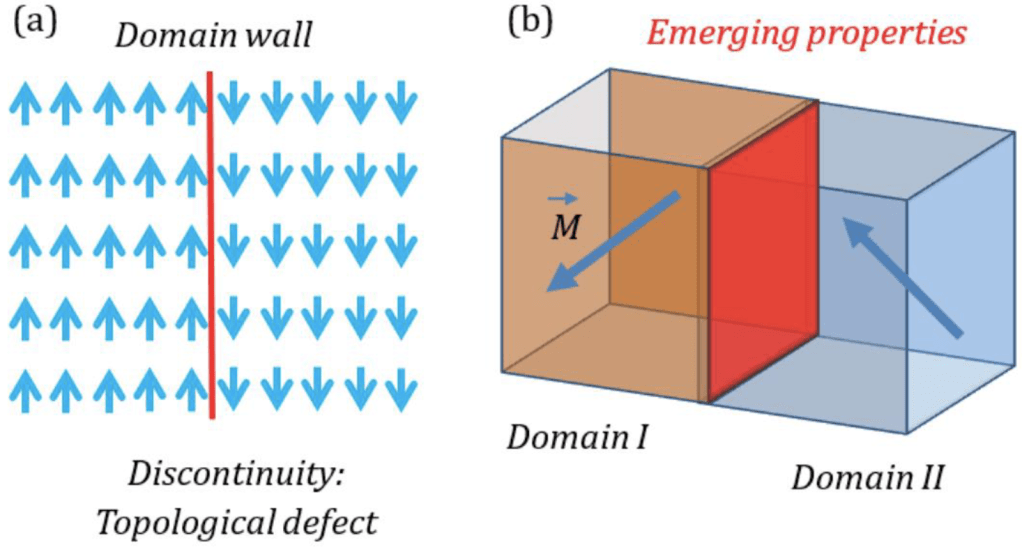

Topological solitons are structures that maintain their shapes even after the material moves through an environment or interacts with other objects. This is an umbrella term that has many different examples; some predominant ones include domain walls, skyrmions, and kinks. Domain walls are boundaries that separate two domains with different orientations [10][11]. Skyrmions are regions that resemble a twisted knot; typically residing in magnetic materials, skyrmions twist the magnetic field [17]. Kinks are areas where the orientation of the material changes abruptly; they are often observed in materials with strong non-linear effects, such as in some types of soliton systems, and can have interesting and useful properties for applications in areas such as data storage and information processing [16]. Topological solitons have been observed in a wide range of physical systems, including magnetic materials [17], superconductors [10], liquid crystals [13], and even biological systems such as DNA [19]. They have important implications for fundamental physics [10][11] as well as potential applications in areas such as data storage, energy conversion, and quantum computing [16].

Figure 6. (a), (b), (c): (a) portrays a domain wall, which separates two areas that have different emergent properties, such as magnetic field or velocity [27]. (b) Displays a skyrmion and an antiskyrmion, the former having a radial direction, and the latter having a partially tangential component [24]. (c) shows a topological kink, which shows an abrupt change in particle density when the two rows begin to overlap [25].

2.5 Modeling Techniques

There are many different techniques for modeling active materials, each with its own advantages and specific uses. The most widely used and versatile methods are agent-based models, continuum models, and particle-based models. These techniques are applicable to a broad range of active materials, from biological tissues to synthetic active matter, and can capture the dynamics of individual agents as well as the collective behaviors of the entire system.

2.5.1 Agent-Based Models

Agent-based models simulate the behavior and interactions of the autonomous components of active matter in a virtual environment in order to study the system as a whole. These simulations treat each element as its own separate entity with individual characteristics and decision-making processes. One of the advantages of agent-based models is that they can capture emergent phenomena, which are patterns or behaviors that arise from the interactions of individual agents but are not explicitly programmed into the model [18]. This makes agent-based models useful for studying complex, dynamic systems that are difficult to analyze using traditional mathematical or statistical methods.

2.5.2 Continuum Models

Continuum models, rather than simulating the individual components of an active matter, instead look at it as a continuous and homogeneous system [12][13]. They are often applied to systems that have a more fluid-like structure, such as fluid dynamics, heat flow, magnetic fields, and electric fields [30]. The main advantage over other models is the ability to study complex phenomena that arise over the entire system, rather than individual elements [7]. Furthermore, they are also computationally efficient, making it possible to simulate large systems or study long-time scales [18].

2.5.3 Particle-based Models

Particle-based models are similar to agent-based ones in that they simulate the individuals of the matter, each with its own velocity, mass, position, etc. The main difference, however, is that agent-based treat the components as decision-making entities, such as animals or bacteria, rather than the inorganic matter seen in active materials. The behavior of each particle is determined by its physical properties and how it interacts with other types of particles [20]. Like agent-based, these are very good for studying the small-scale dynamics of a system [18]. They are also very versatile, as no restrictions are put on the properties of the components or system as a whole [31].

3. Applications

From the evolution of living organisms to the design of modern technological systems, the utilization of active materials has revolutionized the way we perceive and interact with the world around us. These materials, which exhibit dynamic properties and are capable of self-regulating, self-adapting, and self-repairing, have become indispensable in a wide range of applications, ranging from robotics and smart structures to sensors, actuators, drug delivery systems, and energy harvesting devices. By mimicking the sophisticated mechanisms of biological systems, active materials enable the development of intelligent and responsive systems that can autonomously sense and respond to their environment. A comprehensive assessment of the latest advancements and challenges through the exploration of the fundamental principles of active materials, their various natural and synthetic forms, and their applications is necessary to understand the field’s current research landscape.

3.1 Robotics

In recent years, robotics has become one of the most promising areas of application for active materials. With the emergence of soft robotics, which seeks to replicate the flexibility and adaptability of biological organisms, the demand for materials with dynamic and controllable properties has increased significantly [32]. Active materials, with their ability to sense and respond to changes in the environment, offer a new paradigm for designing and controlling robotic systems. From soft grippers that can grasp delicate objects without damaging them to self-healing robots that can recover from damage, the potential applications of active materials in robotics are diverse and far-reaching. In this subsection, we explore the current state of the art in active materials for robotics, highlighting their unique properties and the challenges associated with their integration into robotic systems.

3.1.1 Conventional Robotic Applications

Existing research demonstrates how the idea of a robot can be expanded to include structures with motor capabilities that are capable of structural modification. Preliminary work published by researchers at the California Institute of Technology has demonstrated a multilayer sheet that can be programmed to take on a variety of shapes using liquid crystal elastomers that respond to heat stimuli delivered by stretchy heating coils that are also embedded in the structure. [32] This approach has the potential to address the needs of a range of applications beyond shape changes, such as human-robot interactions and reconfigurable electronics.

As robots are scaled down to millimeter and submillimeter sizes, the fabrication process grows more difficult. Results from recent research suggest a method based on bottom-up assembly and 3D microfabrication to build intricate, 3D magnetically operated small soft machines for biomedical purposes [33]. This progression in the achievable complexity of 3D magnetic soft machines has the potential to improve future capabilities for applications in robotics and biomedical engineering.

By using robotics to fold like origami, organized reconfigurability has been highlighted in recent research [34][35]. Both S. Zhang et al. and D.-Y. Lee et al. present robots that are capable of self-configurations in the form of origami folds, but present this concept in starkly different scales. In the publication by Zhang et al., a small, soft origami robot uses surface topography alteration as an approach to creating a reprogrammable structure. In the latter research by D.-Y Lee et al., transformable wheels were created using a scaled-up version of the origami process in order to achieve the necessary payload for a passenger car. Both papers prove the feasibility and potential applications of robots with adaptive switchable coloration that responds to external thermal and optical stimuli.

Figure 7. Schematic illustrations of programmable and reprocessable multifunctional elastomeric sheets for soft origami robots. (A) Surface morphology–tuned elastomeric sheet via selective UV laser scanning. (B) Structural programming and seamless multi material infusing via local active particle agglomeration. (C) Deformed structures flattened, functional modules erased, and original shape recovered in the solvent.

3.1.2 Self-Assembly

The process of assembly in nature is invariably bottom-up. At the cellular level, animals and plants self-assemble, relying on proteins to self-fold into target geometries that encode all the various activities that keep us alive. Human-architected materials must therefore perform better on their own for an assembly method that is more bio-inspired and bottom-up. There will be some growing pains involved in making such devices scalable, selective, and reprogrammable in a way that could imitate the adaptability of nature. Researchers from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) have made progress in emulating the functionality of natural self-assembly through magnetically reprogrammable materials that self-assemble like robotic cubes [38]. The magnetic programming used in the system is highly selective in what it connects with, enabling robust self-assembly into specific shapes and chosen configurations. The researchers behind this project sourced soft magnetic material from common refrigerator magnets and coated each of the cubes they built with a magnetic signature on each of its faces. The signature ensures that each face is selectively attractive to only one other face from all the other cubes, in both translation and rotation.

Figure 8. Researchers at the CSAIL demonstrated stochastic self assembly using small-scale cubic modules. This was accomplished by magnetically programming module faces with uniquely mating pairs of encodings based on Hadamard matrices. Bounds on this method’s performance are shown. (Below, right)

3.2 Biology

Active materials have attracted increasing interest in biological and biomedical fields due to their ability to mimic and interact with biological systems. The use of active materials in biological systems provides a new level of control and adaptability that traditional materials cannot offer. Active materials can respond to changes in their environment, sense and transmit signals, and even self-repair. These properties make them ideal candidates for a wide range of biomedical applications, from tissue engineering and drug delivery to biosensors and implantable devices. In this subsection, we explore the current applications of active materials in biology and biomedical fields, highlighting their unique properties and advantages over traditional materials. We also discuss the challenges and opportunities associated with the integration of active materials into biological systems and the potential impact of this technology on the future of healthcare and biotechnology.

3.2.1 Medical Applications

A number of research contributions within the field of active material development aim to develop artificial muscles that can efficiently contract and produce actuation forces. Approaches that are bioinspired are frequently used to tackle this problem in an effort to imitate natural muscle performance as closely as possible. Higueras-Ruiz et al. suggest a straightforward and affordable technique based on twisting and coiling that may be used to construct both rotational and translational actuators; the actuator’s appearance is similar to that of an Italian pasta dish called “cavatappi” [36]. The Cavatappi actuator produced contractions that were 10 and 5 times greater than those of human skeletal muscles, respectively, and ones that were above 50% of the original length.

3.2.2 Bioengineering

Inspired by DNA supercoiling, which is the eukaryotic DNA’s 1,000-fold contraction that outperforms skeletal muscles in terms of mass-normalized mechanical work production, researchers have devised novel double helix fibers with contraction strokes as high as 90% [37]. This phenomena uses swelling and deswelling to reversibly convert twists to supercoils. This novel fabrication method improves the applicability of artificial musculature, furthering the possibility of wide rehabilitative usage in the near future.

3.3 Aerospace

The aerospace industry has been a driving force in the development of new materials with improved mechanical and functional properties. Active materials, with their unique ability to respond to changes in the environment, are finding increasing applications in the aerospace engineering sector. The integration of active materials into flight craft offers a new approach to designing and controlling aerospace systems, enabling novel functionalities such as shape-changing wings, adaptive structures, and self-healing composites. In addition to their potential to enhance performance and safety, active materials can also reduce weight, complexity, and maintenance costs. In this subsection, we explore the current state of the art in active materials for aerospace applications, highlighting their unique properties and advantages over traditional materials. We also discuss the challenges and opportunities associated with the integration of active materials into aerospace systems and the potential impact of this technology on the future of air transportation.

3.3.1 Conventional Aircraft

The ability to change the shape of aircraft wings during flight, known as “morphing,” has interested researchers and designers for years as it reduces design compromises. Geometrical parameters that can be affected by morphing include planform alteration, out-of-plane transformation, and airfoil adjustment. However, historically, morphing solutions led to penalties in terms of cost, complexity, or weight. Recent developments in smart materials have the potential to overcome these limitations [39]. Morphing is a promising technology for next-generation aircraft, but many developed concepts have a low technology readiness level, and manufacturers and end-users are still skeptical. Recently, there has been increased focus by researchers on the structural, shape-changing morphing concepts for both fixed and rotary wings, with particular reference to active systems. The weight penalty due to additional actuation systems is a challenge that must be overcome for any successful wing morphing system to be successfully integrated into a functional aircraft.

3.3.2 Spacecraft and Structural Systems

The development of new materials, such as advanced polymer composites and active materials, has allowed for more integration of material, structure, and control system development and application in industries such as aerospace. Without the chance for maintenance, refueling, or repairs, and, for interplanetary probes, spacecraft are expected to travel tremendous distances over extended periods of time without an onboard crew to actively control the spacecraft configuration or flight path. However, space technology has advanced to the point where exploration of other celestial planets, including Mars and the Moon, as well as resource mining in space, are now being seriously considered [40]. These lofty goals necessitate the development of spaceships with self-regulating, self-adaptive, and self-healing behavior.

3.4 Future

The potential applications of active materials are vast and diverse, ranging from biomedical devices and soft robotics to aerospace engineering and energy harvesting. As the field of active materials continues to evolve, new theoretical proposals and innovative applications are emerging, promising to revolutionize the way we interact with and manipulate the world around us. The future of active materials lies in the development of advanced functional materials with tailored properties and in the integration of these materials into sophisticated systems. The challenges in this field are numerous, including the development of efficient manufacturing techniques, the understanding of the complex behavior of active materials, and the integration of these materials into practical devices. In this subsection, we explore the theoretical proposals and emerging applications of active materials, as well as the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead. We discuss the latest advancements in the field and the potential impact of active materials on various industries, emphasizing the need for interdisciplinary collaboration and innovation to fully unlock the potential of this field.

Sources

[1] Zlatanova, S., Rahman, A. A., & Shi, W. (n.d.). Topology For 3D Spatial Objects. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228929271_Topology_for_3D_spatial_objects.

[2] Egenhofer, M., & Herring, J. (1991). Categorizing binary topological relations between regions, lines, and points in geographic databases. The University of Maine.

[3] Pilouk, M. (1996). Integrated modeling for 3D GIS. ITC.

[4] Mesgari, M. S., Choobineh, F., & Reza, A. (2000). Design and implementation of a tetrahedral network (TEN) using a relational database management system for 3D GIS. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 14(2), 143-168.

[5] James, I. M. (1999). History of Topology. Elsevier Science.

[6] Shen, J., Zhou, T., & Chen, M. (2017, February 5). A 27-intersection model for representing detailed topological relations between spatial objects in two-dimensional space. MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/2220-9964/6/2/37.

[7] Bode, N. W., Franks, N. R., Wood, A. J., & Shardlow, T. (2019). Collective animal behavior from Bayesian estimation and probability matching. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(32), 15834-15841.

[8] Budrene, E. O., & Berg, H. C. (1991). Complex patterns formed by motile cells of Escherichia coli. Nature, 349(6310), 630-633.

[9] Gray, C. M., & Singer, W. (1989). Synchronization of oscillatory neuronal responses in cat striate cortex: temporal properties. Visual Neuroscience, 2(2), 203-218.

[10] Kibble, T. W. B. (1976). Topology of cosmic domains and strings. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General, 9(8), 1387. https://doi.org/10.1088/0305-4470/9/8/029

[11] Mermin, N. D. (1979). The topological theory of defects in ordered media. Reviews of Modern Physics, 51(3), 591. https://doi.org/10.1103/revmodphys.51.591

[12] Marchetti, M. C., Joanny, J. F., Ramaswamy, S., Liverpool, T. B., Prost, J., Rao, M., & Simha, R. A. (2013). Hydrodynamics of soft active matter. Reviews of Modern Physics, 85(3), 1143. https://doi.org/10.1103/revmodphys.85.1143

[13] Giomi, L., Bowick, M. J., Ma, X., & Marchetti, M. C. (2013). Defect dynamics in active nematics. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 371(2005), 20120321. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2012.0321

[14] Hirth, J. P., & Lothe, J. (1992). Theory of Dislocations (2nd ed.). Wiley-Interscience. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119312870

[15] Nabarro, F. R. N. (2002). Theory of crystal dislocations (Revised). Dover Publications.

[16] Manton, N. S., & Sutcliffe, P. (2004). Topological solitons. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511617195

[17] Fert, A., Cros, V., & Sampaio, J. (2013). Skyrmions on the track. Nature Nanotechnology, 8(3), 152–156. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2013.29

[18] Wolgemuth, C. W. (2013). Agent-based modeling of biological systems. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering, 15, 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071812-152357

[19] Schwarz, J. M., & Glazier, M. E. (2001). Growth, form, and computers. Nature, 412, 821-828. https://doi.org/10.1038/35090566

[20] Nguyen, N. Q., & Wasikiewicz, S. T. (2018). Particle-based computational modeling of biological systems: A review of methods and applications. Journal of Computational Science, 25, 58-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocs.2017.07.011

[21] Science and SF. (2021, March 20). Scientists propose a new state of matter: an active form of matter they call the swirlonic state.

[22] Sethna, J. P. (n.d.). Topological Defects. https://sethna.lassp.cornell.edu/OrderParameters/TopologicalDefects.html

[23] Mironov, S. A., Petrov, M. I., & Komarov, I. V. (2018). Edge defects in nematic liquid crystals. Physical Review E, 98(2), 022703. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-elementary-topological-defects-a-vortex-b-antivortex-c-positive-edge-defect-d_fig1_307638186

[24] Wikipedia contributors. (2021, April 5). Magnetic skyrmion. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetic_skyrmion

[25] University of Freiburg. (n.d.). Kinks. https://www.qsim.uni-freiburg.de/research/Kinks

Li, Y., & Wu, Y. (2018). Topological defects in the swirlonic state of matter. Physical Review B, 98(21), 214511.

[26] Gao, N., Wang, X., Zhang, Y., Zhang, L., Li, S., & Li, F. (2019). Simulation study on the annihilation and generation of topological defects in the swirlonic state of matter. Journal of Physics Communications, 3(3), 035026. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Simulation-results-with-different-topological-charges-a-c-The-required-compensation_fig3_325929514

[27] Chen, X., & Wu, J. (2022). A Novel High-Precision Image Recognition Algorithm Based on CNN and Multi-Scale Feature Fusion. Symmetry, 14(6), 1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14061098

[28] Rissanen, I., & Laurson, L. (n.d.). Coarsening dynamics of topological defects in thin Permalloy films. Aalto University. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307638186_Coarsening_dynamics_of_topological_defects_in_thin_Permalloy_films

[29] Khan, A. R., Khan, M. A., Qureshi, M. S., & Khan, F. A. (2017). Current status and future challenges of energy storage in smart grid. Heliyon, 3(10), e00414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00414

[30] Vicsek, T., Czirok, A., Ben-Jacob, E., Cohen, I., & Shochet, O. (2012). Active matter: a unified framework for biological motion. Physics Reports, 517(3-4), 71-140.

[31] Marchetti, M. C., Joanny, J. F., Ramaswamy, S., Liverpool, T. B., Prost, J., Rao, M., & Simha, R. A. (2013). The physics of active matter. Reviews of Modern Physics, 85(3), 1143-1189.

[32] Liu, K., Hacker, F., & Daraio, C. (2021). Robotic surfaces with reversible, spatiotemporal control for shape morphing and object manipulation. Science Robotics, 6(53), eabf5116.

[33] Zhang, J., Ren, Z., Hu, W., Soon, R. H., Yasa, I. C., Liu, Z., & Sitti, M. (2021). Voxelated three-dimensional miniature magnetic soft machines via multimaterial heterogeneous assembly. Science robotics, 6(53), eabf0112.

[34] Zhang, S., Ke, X., Jiang, Q., Ding, H., & Wu, Z. (2021). Programmable and reprocessable multifunctional elastomeric sheets for soft origami robots. Science Robotics, 6(53), eabd6107.

[35] Lee, D. Y., Kim, J. K., Sohn, C. Y., Heo, J. M., & Cho, K. J. (2021). High–load capacity origami transformable wheel. Science Robotics, 6(53), eabe0201.

[36] Higueras-Ruiz, D. R., Shafer, M. W., & Feigenbaum, H. P. (2021). Cavatappi artificial muscles from drawing, twisting, and coiling polymer tubes. Science Robotics, 6(53), eabd5383.

[37] Spinks, G. M., Martino, N. D., Naficy, S., Shepherd, D. J., & Foroughi, J. (2021). Dual high-stroke and high–work capacity artificial muscles inspired by DNA supercoiling. Science Robotics, 6(53), eabf4788.

[38] Nisser, M., Makaram, Y., Faruqi, F., Suzuki, R., & Mueller, S. (2022, October). Selective Self-Assembly using Re-Programmable Magnetic Pixels. In 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) (pp. 12659-12666). IEEE.

[39] Barbarino, S., Bilgen, O., Ajaj, R. M., Friswell, M. I., & Inman, D. J. (2011). A review of morphing aircraft. Journal of intelligent material systems and structures, 22(9), 823-877.

[40] Levchenko, I., Bazaka, K., Belmonte, T., Keidar, M., & Xu, S. (2018). Advanced Materials for Next‐Generation Spacecraft. Advanced Materials, 30(50), 1802201.